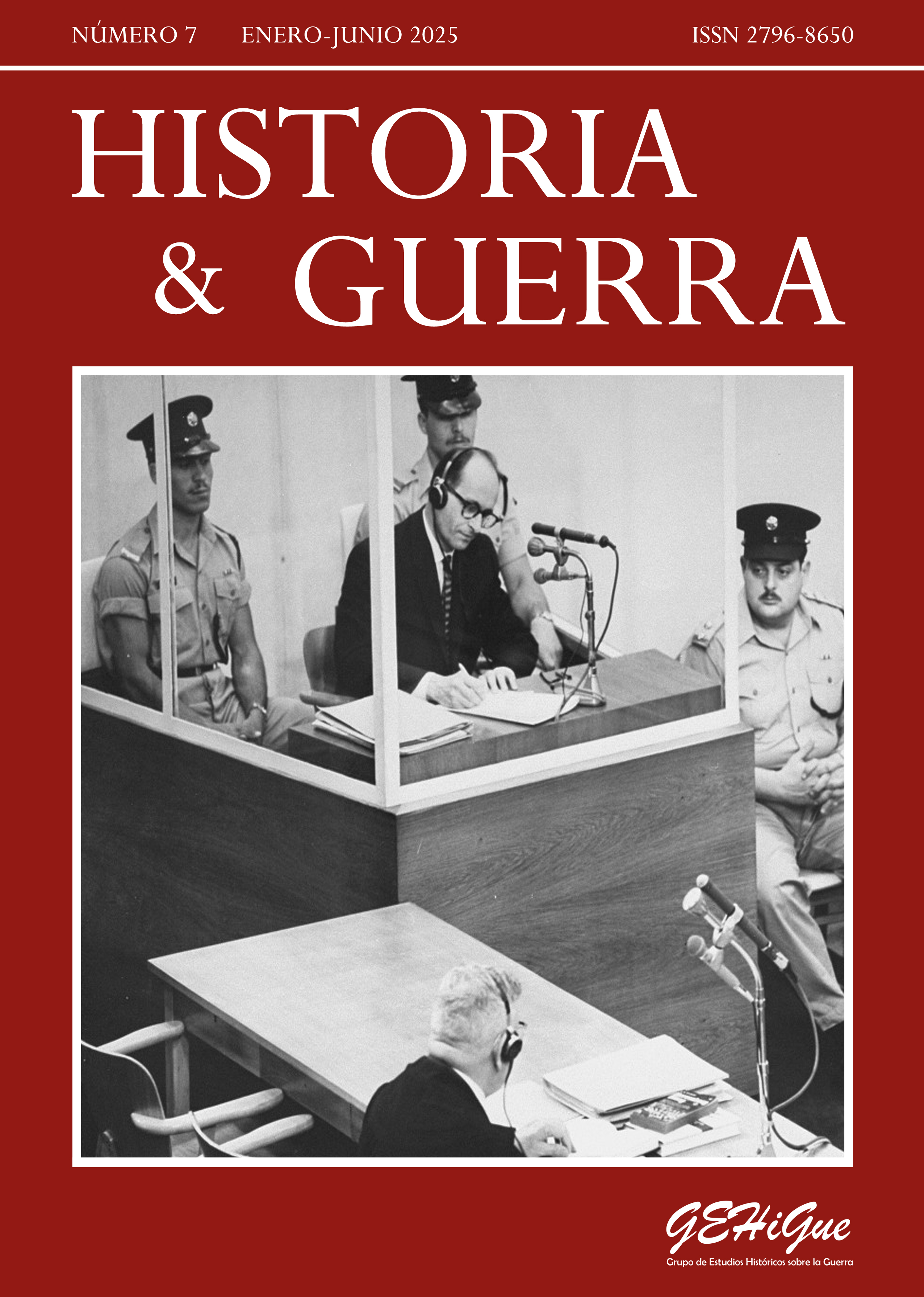

Foreigners in Warsaw during World War II. Passports and false papers, internment, exchange and extermination

Abstract

This paper presents the research findings of a comparative study on the experiences of foreign Jews and Polish dual nationals who were in or passed through Warsaw during World War II. The focus is on Argentines and Americans, briefly referencing those from other countries. It covers both genuine citizens, holders of false papers, and their immediate family members. It analyzes the similarities and differences in the evolution of their treatment after the German occupation and their confinement in the Warsaw Ghetto until the onset of its liquidation (Grossaktion). It also describes the changing policies adopted by the Germans towards these foreigners, which were based on the neutral or belligerent status of the countries they were or claimed to be citizens of. In the case of holders of false papers, it mentions some networks and methods of obtaining them.Downloads

References

After World War II · Jewish Immigration to America. (2023). YIVO Online Exhibitions. https://immigrationusa.yivo.org/exhibits/show/immigrationstories/afterww2

Adler, S. (1982). In the Warsaw Ghetto 1940-1943: An Account of a Witness: The Memoirs of Stanislaw Adler. Yad Vashem.

Baskind, B. (1945). La grande épouvante: souvenirs d'un rescapé du Ghetto de Varsovie. Calmann-Lévy.

Bessette, I. (2010). Not All was Lost. A Young Woman's Memoir. 1939-1946. E-book 978-1-4535-485-4.

Birnbaum, I. (1991). Non Omnis Moriar. No moriré del todo. Memorias de una adolescente en el gueto de Varsovia. Editorial Milá.

Browning, Ch. R. (1978). The final solution and the German Foreign Office: a study of Referat D III of Abteilung Deutschland, 1940-43. Holmes & Meier.

Buergenthal, T. (2003). International law and the Holocaust. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/bib91913

Chenkin, A. y Seligman, B. B. (2008). Jewish Population of the United States, 1953. The American Jewish Yearbook, 55.

Chylinski, T. H. (13 de noviembre de 1941). Poland on Nazi Party. Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/POLAND%20UNDER%20NAZI%20RULE%201941_0001.pdf

Conze, E., Frei, N., Hayes, P. y Zimmermann, M. (2010). Das Amt und die Vergangenheit: deutsche Diplomaten im Dritten Reich und in der Bundesrepublik. Karl Blessing Verlag.

Eisenbach, A. (1988). Kronika getta warszawskiego : wrzesień 1939- styczeń 1943. Czytelnik.

Foreign Relations of the United States, 1939. (1956). General: The British Commonwealth and Europe (Vol. II). M. F. Axton et al. (eds.). Government Printing Office. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1939v02/d615

Gawinecka-Woźniak, M. (2016). The visit of Fritz Henningsen in Warsaw in October 1939 as presented in the diplomat’s account. Zapiski Historyczne, LXXX. https://doi.org/mv9t

Goldstein, B. (1949). The Stars Bear Witness. The Viking Press.

Goldstein, B. (1952). Las estrellas son testigo. Acervo Cultural Editores.

Goñi, U. (2002). La auténtica Odessa. La fuga nazi a la Argentina de Perón. Paidós.

Hilberg, R. (1992). Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders: The Jewish Catastrophe 1933-1945. Harper Collins.

Hilberg, R. (2005). La destrucción de los judíos europeos. Akal.

Hilberg, R., Staron, S. y Kermisz, J. (eds.) (1999) The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow. Prelude to Doom. Ivan R. Dee.

Katsh, A. I. (1965). Scroll of Agony: The Warsaw Diary of Chaim A. Kaplan. Macmillan.

Koblik, S. (1988). The stones cry out: Sweden’s response to the persecution of the Jews, 1933-1945. Holocaust Library.

Langbart, D. A. (1 de abril de 2018). We found ourselves living in the midst of a battlefield: The Experiences of the U.S. Consulate General in Warsaw on the Outbreak of World War II September 1939. American Diplomacy. https://americandiplomacy.web.unc.edu/2018/04/we-found-ourselves-living-in-the-midst-of-a-battlefield/

Langbart, D. A. (18 de mayo de 2021). The Approach of World War II: A View from the U.S. Embassy in Poland. The Text Message. https://text-message.blogs.archives.gov/2016/06/28/the-approach-of-world-war-ii-a-view-from-the-u-s-embassy-in-poland/

Meed, V. (1993). On Both Sides of the Wall: Memoirs from the Warsaw ghetto. Holocaust Library.

New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957. Ancestry. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/3018726820:7488?tid=&pid=&queryId=e9159cc60479ffe313247265df2f6bc4&_phsrc=nlp12&_phstart=successSource

Newton, R. C. (1995). El cuarto lado del triángulo. La “amenaza nazi” en la Argentina (1931-1947). Editorial del Libro.

Perle, Y. (1998). Khurbm Varshe. L’anéantissement de la Varsovie juive. Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah, 3(164), 102-168.

Person, K. (2010). Pawiak w świadomości mieszkańców okupowanej Warszawy. Kwartalnik Historii Żydów, (4), 411-423.

Polonsky, A. (ed.). (1990). A Cup of Tears. A Diary of the Warsaw Ghetto. Basil Blackwell / Institute for Polish-Jewish Studies.

Ras, M. (2020). Meir Berliner: el héroe argentino de Treblinka. Raíces. Revista Judía de Cultura, (124), 81-84.

Ras, M. (2021). Argentinos en Varsovia. 1939-1945 en R. Laham Cohen y E. Caselli (eds.), Antijudaísmo, antisemitismo y judeofobia. De la Antigüedad Clásica al atentado a la AMIA (pp. 199-221). Miño y Dávila editores.

Ras, M. (2023). El rol de Adolf Eichmann y la Embajada argentina en Berlín en la deportación de judíos con ciudadanía argentina. Historia y memoria. Ciclos, (60), 133-169. https://doi.org/mv9v

Rubin, A. (2002). Facts and fictions about the rescue of the Polish Jewry during the Holocaust (vol. 4. The panderers of illusions, the foreign citizenship). Arnon Rubin.

Sarna, J. D. (2014). From World-Wide People to First-World People: The Consolidation of World Jewry en E. Ben-Rafael, J. Bokser Liwerant y Y. Gorny (eds.), Reconsidering Israel-Diaspora Relations (pp. 60-65). Brill.

Schmitz, J. E. y Hart, B. W. (2022). A Crisis of Identity: Good Aliens, Bad Americans, or Bargaining Chips? U.S. Civilian Exchanges with the Third Reich during World War II. The International History Review, 44(6), 1269-1285. https://doi.org/mwbr

Seidman, H. (1997). The Warsaw Ghetto Diaries. Targum Press.

Seidman, N. (1996). Elie Wiesel and the Scandal of Jewish Rage. Jewish Social Studies, 3(1), 1-19.

Shneiderman, S. L. (ed.). (1945). Warsaw Ghetto: a Diary. L. B. Fischer.

Shneiderman, S. L. (ed.). (2007). The Diary of Mary Berg. Growing up in the Warsaw Ghetto. Oneworld.

Shneiderman, S. L. (ed.). (2013). Mary Berg. El gueto de Varsovia. Diario, 1939-1944. Sefarad Editores.

Shulman, A. (ed.). (1982). The Case of Hotel Polski. Holocaust Library.

Simon & Schuster Books. (22 de enero de 2015). History in Five: FDR’s Secret Enemy Exchange Program [Archivo de video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BRAwQLi6vqY

Sloan, J. (ed.). (1958). Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto. The Journal of Emmanuel Ringelblum. Schocken Books.

Szereszewska, H. (1997). Memoirs from occupied Warsaw, 1940-1945. Vallentine Mitchell.

Szlengel, W. “Pasaportes” y “Una cuenta con Dios”. Poemas.

Turkow, J. (1977). Heroicas mujeres del ghetto de Varsovia. Biblioteca Popular Judía.

Turkow, I. (1995). C'était ainsi, 1939-1943: la vie dans le ghetto de Varsovie. Austral.

Walser, R. (2023). War Comes to Warsaw: September 1939. American Foreign Service Association. https://afsa.org/war-comes-warsaw-september-1939

Woods, R. B. (1975). Decision-Making in Diplomacy: The Rio Conference of 1942. Social Science Quarterly, 55(4), 901-918.

Zuckerman, Y. (1993). A surplus of memory: chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. University of California Press.

Copyright (c) 2025 Marcia Ras, Samara Rose Angel

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Historia & Guerra uses an international license Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0).

You are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format.

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material.

- The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms..

Under the following terms:

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

Notices:

You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation.

No warranties are given. The license may not give you all of the permissions necessary for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy, or moral rights may limit how you use the material.

The author retains all rights to his work without restriction and grants Historia & Guerra the right to be the first publication of the work. Likewise, the author may establish additional agreements for the non-exclusive distribution of the version of the work published in the Journal (for example, placing it in an institutional repository or publishing it in a book), with the acknowledgment of having been first published in this journal. Use of the work for commercial purposes is not permitted.

.jpg)