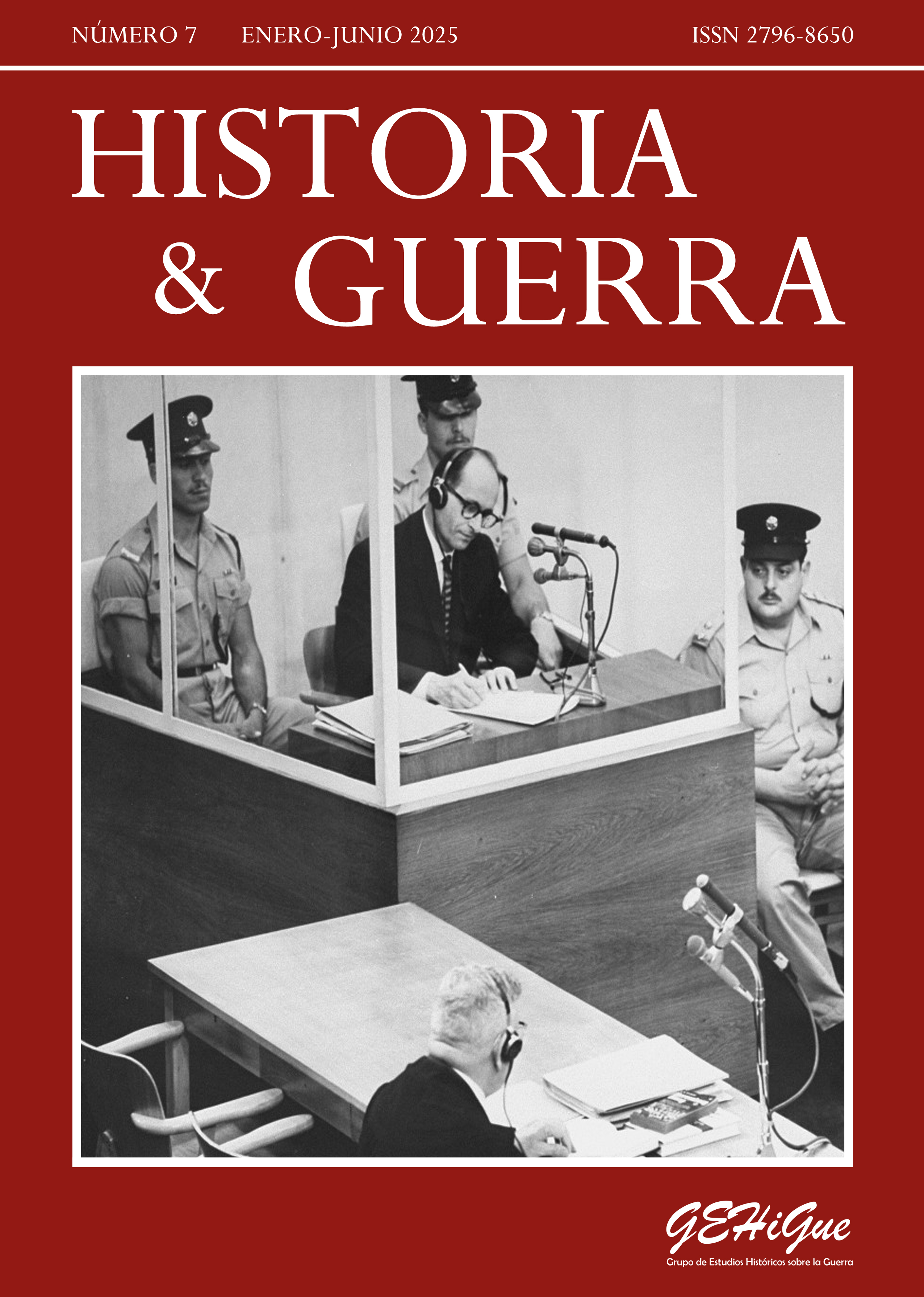

Reporting in exile: the periodistic contribution of Livia Neumann in the Argentinisches Wochenblatt

Abstract

After the rise of National Socialism in 1933 and the invasion of its troops over European territory, Argentina became a transcendental node of German-speaking exile. Around 40,000 emigrants arrived on the shores of Buenos Aires during the period 1933-1945. One of the exiles who arrived in Argentina was Livia Neumann, who was quickly inserted in the main German-language anti-Hitlerist periodical in Latin America, the Argentinisches Tageblatt. The following article aims to recover the journalistic work of the exiled Livia Neumann published in the weekly Argentinisches Wochenblatt –sister publication of the newspaper– during the period 1938-1939. In detail, how this particular aspect of her work in the Alemann family’s periodicals is a historical testimony that allows us to approach different aspects of the German-speaking exile in the region. For this, we will focus on three aspects: 1) Her concern to inform about the consequences of the National Socialist advance on Europe, 2) the reproduction of migrant testimonies that show the delicate social and juridical conditions of the German-speaking exile and 3) the denunciation of the Nazi crimes in the concentration camps.Downloads

References

Agüero, A. C., y García, D. (2013). Culturas locales, culturas regionales, culturas nacionales. Cuestiones conceptuales y de método para una historiografía por venir. Prismas. Revista de Historia Intelectual, (17), 181-185.

Birgit, F. (1989). Publizistinnen und Publizisten aus Österreich im argentinischen Exil. Mitteilungen des Instituts für Wissenschaft und Kunst, (3), 7-17.

Borstendoerfer, A. (1945). Los últimos días en Viena. Calomino.

Bryce, B. (2008). Germans in Ontario and Buenos Aires, 1905-1918: Das Argentinische Tageblatt and Das Berliner Journal’s Discourse about Ethnicity and Its Changes During World War I [Tesis de Maestría]. York University.

Bryce, B. (2018). Ser de Buenos Aires: alemanes, argentinos y el surgimiento de una sociedad plural 1880-1930. Editorial Biblos.

Cartolano, A. (1999). Editoriales en el exilio: los libros en lengua alemana editados en la Argentina durante el periodo 1930-1950 en R. Rohland de Langbehn (Hg.), Paul Zech y las condiciones del exilio en la Argentina: 1933-1946 (pp. 81-92). Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Efron, G. y Brenman, D. (2006). Los medios gráficos argentinos durante el nazismo. Question/Cuestión, 1(11).

Friedmann, G. (2009). La cultura en el exilio alemán antinazi. El Freie Deutsche Bühne de Buenos Aires, 1940-1948. Revista Anuario IEHS, (24), 69-87.

Friedmann, G. (2010). Alemanes antinazis en Argentina. Siglo XXI.

Friedmann, G. (2011). Educación, política e identidad. La escuela Pestalozzi de Buenos Aires entre 1934 y 1945. Iberoamericana, 11(43), 61-77.

Friedmann, G. (2012). Los judíos de habla alemana y las identidades judeoalemanas en Buenos Aires durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Estudios Migratorios Latinoamericanos, 25(71), 293-312.

Friedmann, G. (2015). El Frente Negro en la Argentina durante la década de 1930. Iberoamericana, 15(57), 39-57.

Friedmann, G. (2016). Nacionalsocialistas anti-hitleristas y cuestión judía: Los casos de Die Schwarze Front y Frei-Deutschland Bewegung en la Argentina. Anuario IEHS, 31(1), 15-36.

Friedmann, G. (2018a). El impacto del nacionalsocialismo en el semanario Der Russlanddeutsche, 1933-1939. Boletín del Instituto de Historia Argentina y Americana. Dr. Emilio Ravignani, (49), 117-144.

Friedmann, G. (2018b). El antisemitismo en la prensa en alemán de la Argentina, 1933-1941. Ayer, (111), 283-312.

Friedmann, G. (2022). La construcción de la “comunidad del pueblo” nacionalsocialista en la Argentina. Iberoamericana, 22(81), 145-166.

Friedmann, G. (2023). De nacionalsocialista revolucionario a militante antifascista. La trayectoria de Bruno Fricke durante las décadas de 1930 y 1940. Cuadernos de Historia. Serie Economía y Sociedad, (31), 32-57.

Garnica de Bertona, C. (2010). Livia Neumann, novelista en R. Rohland de Langbehn y M. Vedda (eds.), Anuario Argentino de Germanística. La emigración alemana en la Argentina (1933-1945). Su impacto cultural (II, pp. 213-220). Asociación Argentina de Germanistas.

Garnica de Bertona, C. (2016). Literatura en Alemán de Migrantes y Viajeros a la Argentina (1870-1970). Publicia.

Glocer, S. y Kelz, R. (2014). Paul Walter Jacob y las músicas prohibidas durante el nazismo. Gourmet Musical.

Groth, H. (1996). Das Argentinische Tageblatt. Sprachrohr der demokratischen Deutschen und der deutsch-jüdischen Emigration. LIT Verlag.

Hock, B. (2016). In zwei Welten: Frauenbiografien zwischen Europa und Argentinien: deutschsprachige Emigration und Exil im 20. Jahrhundert. Edition tranvía, Verlag Walter Frey.

Hoffmann, K. (2009). ¿Construyendo una “comunidad”? Theodor Alemann y Hermann Tjarks como voceros de la prensa germanoparlante en Buenos Aires, 1914-1918. Iberoamericana, 9(33), 121-137.

Ismar, G. (2006). Der Pressekrieg: Argentinisches Tageblatt und Deutsche La Plata Zeitung 1933-1945. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin.

Kelz, R. V. (2010). Competing Germanies: The Freie Deutsche Buehne and the Deutsches Theater in Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1938-1965 [tesis doctoral]. Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University.

Kießling, W. (1984). Kunst und Literatur im antifaschistischen Exil 1933-1945. Exil in Lateinamerika. Reclams Universal-Bibliothek.

Kohut, K. y Mühlen, P. V. Z. (1994). Alternative Lateinamerika: das deutsche Exil in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. Alternative Lateinamerika. Vervuert Verlag.

Laberenz, L. (2008). Vom Kaiser zum Führer-Deutschsprachige Nationalismusdiskurse in Buenos Aires 1918-1933. GRIN Verlag.

Lvovich, D. (2003). Nacionalismo y antisemitismo en la Argentina. Javier Vergara Editor.

Maas, L. (1978). Deutsche Exilpresse in Lateinamerika (Vol. 3). Buchhändler-Vereinigung.

Münster, I. (2011). Librerías y bibliotecas circulantes de Judíos Alemanes en la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, 1930-2011. Estudios Migratorios Latinoamericanos, 25(70), 157-175.

Newton, R. (1977). German Buenos Aires, 1900-1933: Social Change and Cultural Crisis. Austin & London.

Newton, R. (1995). El cuarto lado del triángulo. La «amenaza nazi» en la Argentina (1931-1947). Sudamericana.

Rohland de Langbehn, R. (2023). Argentinische Publikationen in deutscher Sprache. Ein Katalog / Publicaciones argentinas en lengua alemana. Un catálogo. Centro DIHA.

Saint Sauveur-Henn, A. (1995). Un siècle d’émigration allemande vers l’Argentine 1853-1945. Böhlau.

Saint Sauveur-Henn, A. (2002). Exotische Zuflucht? Buenos Aires, eine unbekannte und vielseitige Exilmetropole (1933-1945) en C. D. Krohn (ed.), Metropolen des Exils. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Schoepp, S. (1996). Das «Argentinische Tageblatt» 1933 bis 1945. Ein Forum der antinationalsozialistischen Emigration. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin.

Spitta, A (1999). El Argentinisches Tageblatt como vocero del exilio alemán en la Argentina, 1933 a 1945 en R. Rohland de Langbehn (Hg.), Paul Zech y las condiciones del exilio en la Argentina: 1933-1946 (pp. 51-65). Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Tato, M. I. (2007). El ejemplo alemán: La prensa nacionalista y el Tercer Reich. Revista Escuela de Historia, (6), 34-60.

Tato, M. I. (2017). La trinchera austral. La sociedad argentina ante la Primera Guerra Mundial. Prohistoria.

Trapp, F. (2019). Teatro y política: el Freie Deutsche Bühne de Buenos Aires en S. Carreras (ed.), Identidad en cuestión y compromiso político: los emigrados germanohablantes en América del Sur (pp. 139-155). Iberoamericana.

Von zur Mühlen, P. (1988). Fluchtziel Lateinamerika: die deutsche Emigration 1933-1945: politische Aktivitäten und soziokulturelle Integration. Verlag Neue Gesellschaft.

Walter, H. A. (1978). Deutsche Exilliteratur 1933-1950 (Band 4. Exilpresse). Springer Verlag.

Wechsler, W. (2018). La historia de la memoria del Holocausto en Argentina. Cuadernos Judaicos, (35), 261-283.

Copyright (c) 2025 Tomás Schierenbeck Molina

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Historia & Guerra uses an international license Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0).

You are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format.

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material.

- The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms..

Under the following terms:

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

Notices:

You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation.

No warranties are given. The license may not give you all of the permissions necessary for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy, or moral rights may limit how you use the material.

The author retains all rights to his work without restriction and grants Historia & Guerra the right to be the first publication of the work. Likewise, the author may establish additional agreements for the non-exclusive distribution of the version of the work published in the Journal (for example, placing it in an institutional repository or publishing it in a book), with the acknowledgment of having been first published in this journal. Use of the work for commercial purposes is not permitted.

.jpg)